3003, 1050, 1060 Aluminum Sheet Plate

Aluminum sheet and plate often get introduced as if they were interchangeable-bright metal, lightweight, easy to form, broadly "corrosion resistant." But the most practical way to understand common grades like 3003, 1050, and 1060 is to treat them as three different personalities that happen to wear the same silver suit. When you specify them correctly, they behave predictably in fabrication, finishing, and service. When you swap them casually, the shop floor reminds you that chemistry and temper are not marketing details; they are performance settings.

From the viewpoint of a fabricator who wants smooth bending, stable punching, clean anodizing, and minimal surprises after installation, these three alloys form a useful triangle. 1050 and 1060 sit in the "near-pure" aluminum family, where conductivity and reflectivity feel almost like the point of the material. 3003 lives in the aluminum-manganese family, where modest alloying brings strength and better tolerance for real-world forming and handling. None is "better" in the abstract; each becomes better when the job is described honestly.

The chemistry story, told plainly

1050 and 1060 are part of the 1xxx series: they are essentially aluminum with small controlled limits on impurities. That purity gives them excellent electrical and thermal conductivity, high corrosion resistance in many environments, and great response in applications where "clean metal" matters-heat exchangers, reflectors, food-related equipment, and decorative anodized surfaces where uniformity is valued.

1060 is typically purer than 1050, and that small difference matters in conductivity and some finishing outcomes, but it can also mean slightly lower strength in comparable tempers. 3003, by contrast, contains manganese as the primary alloying element. Manganese doesn't turn aluminum into a high-strength structural grade, but it makes it noticeably more robust than near-pure aluminum in everyday fabrication: better dent resistance, better performance in drawn parts, and a wider comfort zone for general sheet-metal work.

Typical chemical composition limits (reference ranges)

Actual limits depend on the specific standard and supplier certification. Always confirm with mill test certificates for critical work.

| Alloy | Al (min) | Mn | Si | Fe | Cu | Zn | Others (each / total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1050 | ≥ 99.50% | ≤ 0.05% | ≤ 0.25% | ≤ 0.40% | ≤ 0.05% | ≤ 0.07% | ≤ 0.05% / ≤ 0.15% |

| 1060 | ≥ 99.60% | ≤ 0.03% | ≤ 0.25% | ≤ 0.35% | ≤ 0.05% | ≤ 0.05% | ≤ 0.03% / ≤ 0.10% |

| 3003 | Balance | 1.0–1.5% | ≤ 0.60% | ≤ 0.70% | 0.05–0.20% | ≤ 0.10% | ≤ 0.05% / ≤ 0.15% |

A useful mental shortcut is this: if you want conductivity and surface "purity," lean toward 1050/1060; if you want practical strength with friendly forming, 3003 is often the calmer choice.

Temper is not a suffix; it's the behavior

Many purchasing disputes happen because "3003 sheet" was ordered without temper clarity, then the shop tried to bend it like annealed material and it cracked, or it was too soft and oil-canned after assembly. Temper defines how the material was strain-hardened or annealed, and it changes yield strength, elongation, springback, and forming limits.

Common tempers you'll see in these alloys include O (annealed), H12/H14/H16/H18 (strain-hardened to increasing strength), and H24 (strain-hardened and partially annealed). In practice:

- O temper is the most formable, best for deep drawing, complex bends, and tight radii, but it scratches and dents more easily.

- H14 is a workhorse temper for sheet metal. It balances formability with stiffness and is frequently stocked.

- Higher H tempers like H18 resist denting and feel stiffer, but the bend radius requirements increase and cracking risk rises, especially across the rolling direction.

For 3003, H14 is a common "default" because it bends well while staying stable in panels. For 1050 and 1060, O and H14 are common depending on whether the goal is forming or flatness/stiffness.

Mechanical and physical properties you can actually use

Exact properties vary with temper and thickness, but some practical anchors help with selection.

- 3003 generally has higher strength than 1050/1060 at the same temper, with good elongation in soft tempers. It's often chosen for general fabrication, housings, cladding, roofing, and heat exchanger fins where strength and formability both matter.

- 1050 and 1060 are softer at comparable tempers, but they excel in conductivity and corrosion resistance, and they can produce very consistent surface appearance after finishing.

For thermal and electrical considerations, 1xxx alloys usually outperform 3003. If the part is a heat spreader, busbar-like element, or reflector, 1060 (and sometimes 1050) earns its place even if you need a thicker gauge to compensate for lower strength.

Standards and what to put on a purchase order

A reliable order is specific about alloy, temper, thickness tolerance, surface condition, and applicable standards. Common implementation standards include ASTM and EN systems. Depending on region and application, you'll see:

- ASTM B209 for aluminum and aluminum-alloy sheet and plate (widely used in North America and beyond)

- EN 485 for aluminum and aluminum alloy sheet, strip, and plate (common in Europe)

- JIS H4000/H4160 family for Japanese industrial specifications in certain markets

For practical procurement, include:

- Alloy and temper, such as 3003-H14, 1050-O, 1060-H24

- Thickness, width, length, and tolerance class if required

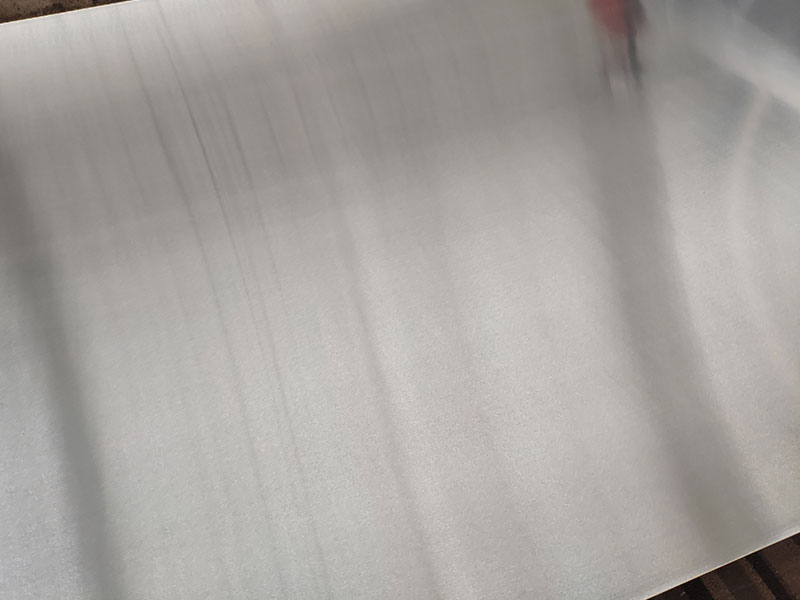

- Surface finish requirement, such as mill finish, brushed, or coated

- Protective film requirement if the surface is decorative or will be anodized

- Flatness expectations, especially for laser cutting or panel applications

- Certification needs, such as MTC with chemical and mechanical results, and RoHS/REACH if applicable

Forming, welding, and finishing: where the differences show up

In bending and general forming, 3003 tends to be forgiving. It handles moderate forming without demanding extreme radii, especially in softer H tempers. It also often feels "less gummy" than near-pure aluminum in punching and shearing, though tooling and lubrication still matter.

1050 and 1060 can feel very soft in O temper and may mark easily. In stamping and deep drawing, that softness can be an advantage if the tool design supports it, but it also means you must manage surface protection and handling. If cosmetic quality matters, specify protective film and avoid rough roller tables.

For welding, all three are generally weldable, but the performance requirement should drive the selection of filler and process. Near-pure alloys and 3003 are commonly welded in general fabrication, but if the weld is part of a pressure-containing design or code-regulated system, involve the welding engineer early and align alloy, filler, and procedure qualifications accordingly.

For anodizing and decorative finishing, 1050 and 1060 often give a clean, bright result because of their purity, while 3003 can show a slightly different tone due to manganese and minor constituents. If color matching is critical across multiple parts, avoid mixing alloys in visible assemblies or run qualification samples.

Typical applications, interpreted as intent

3003 is the choice when the part must survive handling, vibration, and daily use with fewer dents and less waviness, while still being easy to form. It's a natural fit for cladding, appliance panels, general enclosures, roofing and wall systems, and HVAC components.

1050 is a practical "pure aluminum" option when cost matters but you still want strong corrosion resistance and good conductivity. It's common in chemical equipment liners, reflectors, signage bases, and general-purpose forming.

1060 tends to be selected when you want to push conductivity and surface consistency a bit further, often in electrical and thermal applications, lighting reflectors, and certain heat transfer parts.

Choosing between them without overthinking

If you need a reliable sheet that bends nicely and feels sturdy in the hand, 3003-H14 is often the sensible baseline. If the part's purpose is to move heat or electricity, or to present a bright, consistent finished surface, 1050 or 1060 in the right temper is usually the better conversation. And when someone says "they're basically the same," it's worth replying from the shop's point of view: they may look the same on the rack, but they do not behave the same in the press brake, the anodizing tank, or the field.

In the end, 3003, 1050, and 1060 are less like competing products and more like three dialects of aluminum. Speak the one your application understands-by specifying chemistry, temper, and standards clearly-and the material will answer with predictable performance.

https://www.aluminumplate.net/a/3003-1050-1060-aluminum-sheet-plate.html