Why aluminum bubble

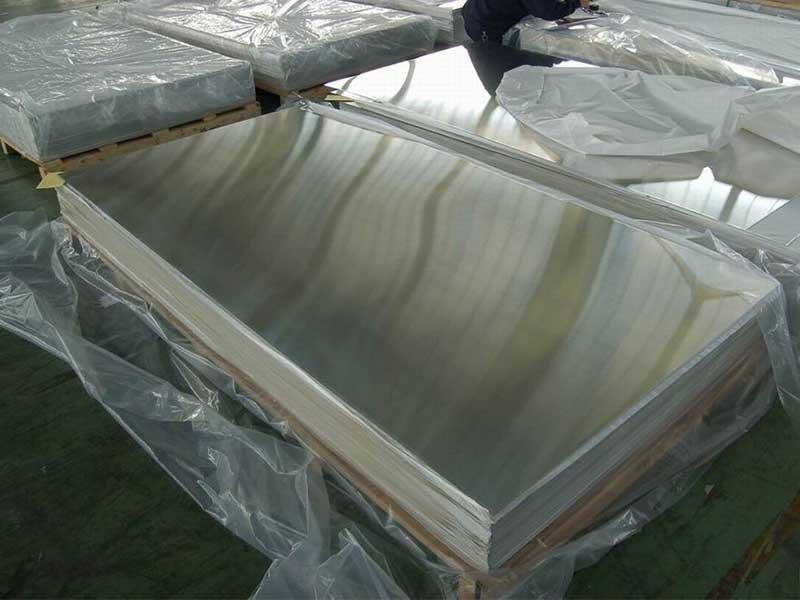

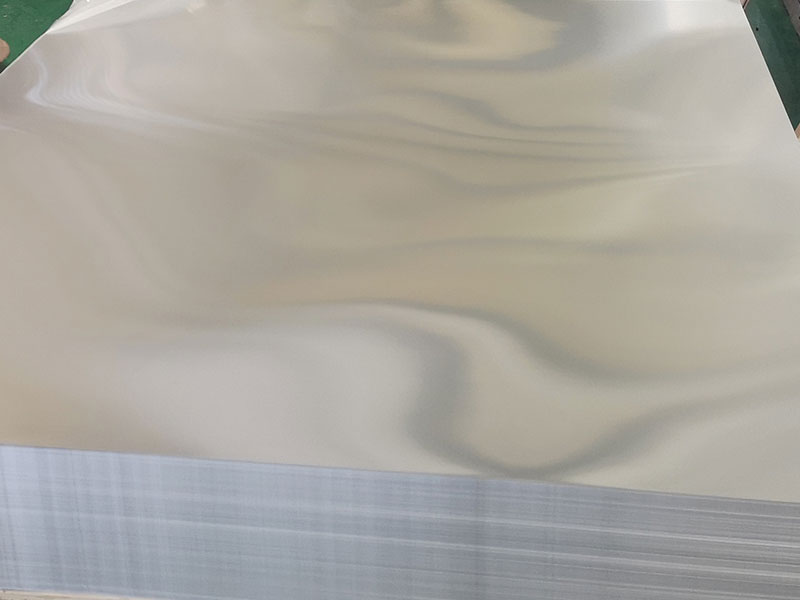

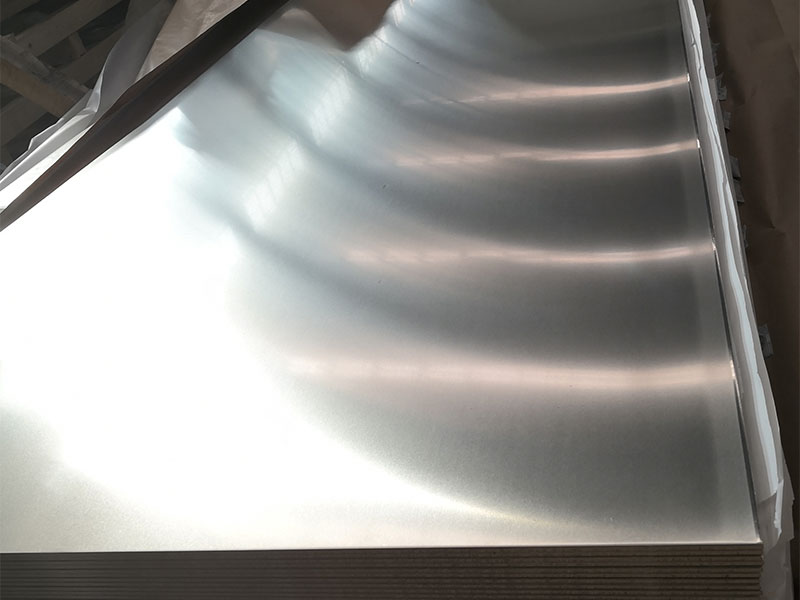

People often describe a surface defect on aluminum sheet as "bubbling," as if the metal were alive and exhaling. From a distance it can look that way: small domes, blisters, or raised patches that appear after rolling, forming, painting, powder coating, anodizing, or even during service. From a materials perspective, though, aluminum doesn't bubble in the way liquids do. What you're seeing is the sheet revealing something that was already inside it-gas, moisture, inclusions, contamination, or unstable interfaces-pushed outward by heat, pressure, or chemistry.

A unique way to understand aluminum bubbling is to treat the sheet like a sealed envelope. If anything inside that envelope expands, reacts, or loses adhesion when the envelope is heated or deformed, it tries to create space. The result is a blister.

What "Bubbling" Looks Like in Aluminum Sheet

In real production, "aluminum bubble" can refer to several related phenomena:

Raised blisters after painting or powder coating, often noticeable after oven curing

Blistering after anodizing, sometimes localized along rolling direction

Bulges after deep drawing, stamping, or bending

Subsurface delamination that becomes visible only after heat exposure

Although the appearance can be similar, the root causes differ. The is when the bubbles appear: before coating, during forming, during cure, or after exposure in the field.

The Main Causes, Explained as "Pressure + Weak Spot"

Aluminum bubbling almost always needs two ingredients.

Pressure source: something that expands or generates gas

Weak spot: an interface or defect that can separate

Hydrogen and moisture: the classic pressure source

Hydrogen is the most common gas involved in blistering. It can be introduced during melting, casting, improper degassing, wet scrap, lubricants, or water contamination. Hydrogen is soluble in liquid aluminum but much less soluble in solid aluminum, so during solidification it can form porosity. That porosity may stay invisible until later processing, when heat makes gas expand.

In coating lines, moisture or solvent trapped under a coating can also generate pressure during curing. If pretreatment and drying are not controlled, the coating becomes the "envelope," and the trapped volatiles become the "pressure."

Rolling, annealing, and trapped defects: the weak spot

Even when porosity is present, you might not see bubbles until rolling, annealing, or solution heat treatment. Rolling can elongate voids. Annealing can allow gas to coalesce. Solution heat treatment for heat-treatable alloys can expand internal defects enough to show up as blisters, especially on thicker sheet or plate.

Weak spots can also be created by non-metallic inclusions, oxide films, or poor bonding from casting defects. If an oxide "film" is folded into the metal during casting or hot rolling, it acts like a pre-made crack plane. Heat and pressure then lift the surface into a blister.

Surface contamination: when the bubble is actually a coating failure

Many "bubbles" reported by end users are coating blisters rather than metal blisters. The metal may be fine, but the interface between aluminum and coating fails due to oils, rolling lubricants, fingerprints (chlorides), insufficient conversion coating, or improper anodizing sealing. When the coating loses adhesion, any internal vapor pressure makes the blister visible.

Alloy and Temper: Why Some Sheets Bubble More Than Others

Different aluminum alloys and tempers behave differently because they differ in composition, precipitation behavior, and typical processing routes.

Non-heat-treatable alloys (1000, 3000, 5000 series) often have excellent formability and are commonly used in sheet. Bubbling in these families is frequently linked to casting/rolling cleanliness, hydrogen porosity, or coating-process issues rather than heat-treatment blisters.

Heat-treatable alloys (2000, 6000, 7000 series) may be more sensitive to blistering during solution heat treatment or high-temperature exposure. If internal porosity exists, the higher thermal cycles can make it show up. In 6xxx alloys used for automotive and architectural sheet, blistering is sometimes discovered after paint bake cycles if pretreatment and substrate cleanliness are not aligned.

Temper also matters. Fully annealed O temper is softer, forms easily, and can "mask" internal defects until later heating. H tempers (strain-hardened) have different residual stresses that can influence how defects open during forming. T tempers (heat-treated) require thermal steps that can trigger blisters if internal gas is present.

Common sheet tempers and what they imply:

O temper: annealed, best formability, but later heating can reveal latent porosity

H14/H24: strain hardened (and partially annealed for H24), stable for forming; blistering usually points to substrate defects or surface prep/coating issues

T4/T6 (typical for 6xxx): involves solution treatment and aging; heat exposure can reveal internal gas-related blisters if quality is inconsistent

Parameters That Influence Blister Risk in Practice

Blistering is not random; it responds to measurable parameters.

Temperature and soak time are the biggest triggers. Higher cure temperatures, longer dwell times, and faster ramp rates increase internal pressure and soften the metal/coating interface.

Sheet thickness matters. Thicker sheet traps heat gradients and can contain larger casting-related pores, while thin gauge can be more sensitive to surface contamination because the coating-to-substrate ratio is higher.

Surface roughness and cleanliness are decisive in coating blistering. Roughness influences wetting; contamination reduces adhesion. Pretreatment chemistry and deionized water quality strongly influence blister resistance.

Forming severity matters. Deep drawing and tight-radius bending can open subsurface laminations or porosity, turning an invisible defect into a visible dome.

Implementation Standards and Quality Control Touchpoints

In production and purchasing, blister control is best handled by linking the aluminum sheet specification to recognized standards and process checks.

Aluminum sheet and plate are commonly supplied to ASTM B209 (or EN 485 series in Europe), which define chemical composition, mechanical properties, and dimensional tolerances. For aerospace or high-reliability uses, additional requirements for internal quality may be specified.

For coatings, pretreatment and testing standards are just as important. Conversion coatings and anodizing are typically controlled by process specifications, and blister resistance is often checked with humidity testing, salt spray testing, or adhesion tests after cure.

Practical controls that reduce bubbling risk include melt degassing, filtration, clean casting practices, ultrasonic inspection for critical plate, controlled rolling and annealing schedules, and disciplined pretreatment/drying before coating.

Chemical Properties Table (Typical Composition, wt.%)

Below is a concise reference for common aluminum sheet alloys. Values are typical maximums or ranges per common standards; exact limits depend on the governing specification (ASTM B209, EN 573, etc.).

| Alloy | Si (%) | Fe (%) | Cu (%) | Mn (%) | Mg (%) | Zn (%) | Cr (%) | Ti (%) | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1050 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | - | 0.03 | Balance |

| 1060 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | - | 0.03 | Balance |

| 1100 | 0.95 (Si+Fe) | - | 0.05–0.20 | 0.05 | - | 0.10 | - | - | Balance |

| 3003 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.05–0.20 | 1.0–1.5 | - | 0.10 | - | - | Balance |

| 5052 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 2.2–2.8 | 0.10 | 0.15–0.35 | - | Balance |

| 5083 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.40–1.0 | 4.0–4.9 | 0.25 | 0.05–0.25 | 0.15 | Balance |

| 6061 | 0.4–0.8 | 0.70 | 0.15–0.40 | 0.15 | 0.8–1.2 | 0.25 | 0.04–0.35 | 0.15 | Balance |

| 6063 | 0.2–0.6 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.45–0.9 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | Balance |

The Customer-Facing Takeaway: Bubbling Is a "System" Problem

From the perspective of the sheet, bubbling is rarely caused by a single factor. It's usually the interaction between substrate quality, thermal history, surface preparation, and the finishing process. If you want blister-free results, align these elements:

Choose a suitable alloy and temper for the forming and heating steps you will use

Specify standards clearly (ASTM B209 / EN 485) and add internal quality requirements when necessary

Control heat cycles in curing or solution treatment and avoid trapping moisture/solvents

Demand strong surface cleanliness and pretreatment consistency before coating or anodizing

When aluminum "bubbles," it's not misbehaving-it's communicating. The sheet is telling you where gas was trapped, where adhesion was weak, or where process chemistry and temperature pushed the material past a quiet limit. Listening to that message is how you turn a cosmetic defect into a controllable variable.