Digital Printing Plate For Offset Printing Machine PS CTP CTCP Plate

Digital Printing Plate For Offset Printing Machine PS CTP CTCP Plate

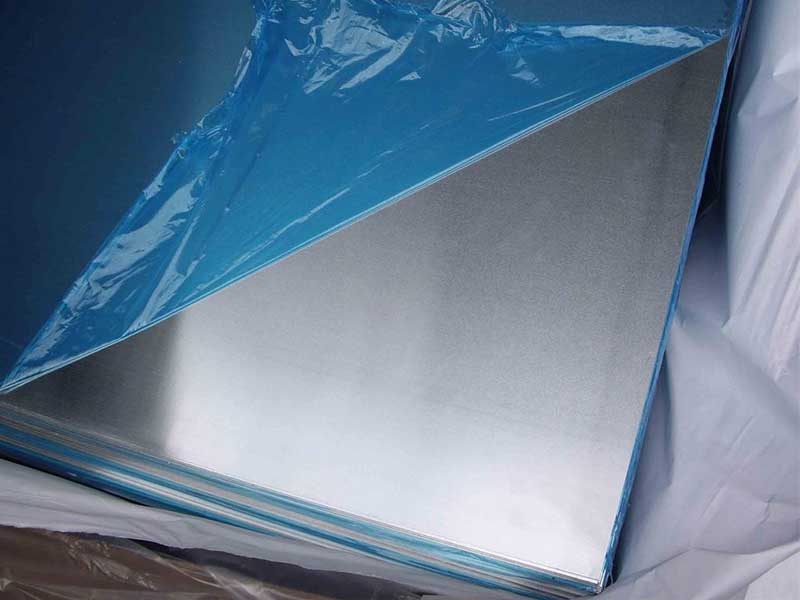

In most print shops, the aluminum plate rack sits quietly against the wall, overshadowed by the big, noisy offset presses. Yet that thin aluminum sheet – the printing plate – decides whether a print run is profitable, stable, and sharp or a slow bleed of time and money. Looking at offset plates from the inside out, especially through the lens of aluminum metallurgy and surface chemistry, offers a surprisingly fresh way to understand PS, CTP, and CTCP plates and why they behave so differently on press.

The Aluminum Core: More Than Just a Substrate

At the heart of almost every professional offset printing plate is aluminum, generally a high‑purity, non-heat-treatable alloy in the 1xxx or 3xxx series. The choice is deliberate. A plate has to be flat, dimensionally stable, and resistant to corrosion, yet soft enough to be grained, anodized, and coated with precision.

A typical base alloy for printing plates falls close to the 1050 or 3003 family:

- Aluminum (Al): balance, usually above 98.5%

- Silicon (Si): ≤ 0.25%

- Iron (Fe): ≤ 0.40%

- Copper (Cu): ≤ 0.05% (kept low to reduce corrosion)

- Manganese (Mn): up to about 0.3–0.6% when a 3xxx alloy is used for added strength

- Magnesium (Mg): ≤ 0.05%

- Zinc (Zn): ≤ 0.10%

- Titanium (Ti): ≤ 0.05%

The temper usually sits around H14–H16, a half‑hard to hard rolled condition. This gives enough rigidity to resist bending in high‑speed plate cylinders but enough ductility to avoid cracking at the clamps. The aluminum strip is manufactured to tight tolerances in thickness – commonly 0.14–0.30 mm – with flatness and residual stress controlled so it wraps the press cylinder without distortion.

Think of the plate as a layered system instead of a single product: alloy core, micro-structured surface, anodic oxide layer, chemical conversion, and photosensitive or photopolymer coating. PS, CTP, and CTCP categories differ mainly in that last, ultra-thin functional layer, but everything underneath is what makes that coating behave.

Surface Engineering: From Smooth Foil to Lithographic Plate

Raw aluminum sheet is almost useless for offset printing. Its surface must be engineered so that it holds water where needed and repels ink where it shouldn’t print, while doing the opposite in the image areas.

The process typically runs through three crucial steps.

Mechanical or electrochemical graining

The surface is roughened with a finely controlled texture. Electrochemical graining in nitric or hydrochloric based electrolytes is standard for high-quality plates. The grain size, depth, and distribution affect water retention, ink acceptance, and dot gain. Too coarse, and fine dots break up; too fine, and water balance becomes unstable.

Anodizing

The grained sheet is anodized in a sulfuric acid bath. The aluminum surface is converted into a porous aluminum oxide layer – thin, hard, hydrophilic, and chemically uniform. Thickness usually ranges from about 1.5 to 3.0 µm, depending on plate grade and durability requirements. Higher thickness generally means longer run length and better abrasion resistance but also more energy consumption and stricter process control.

Hydrophilizing / sealing

A post-treatment, often with silicates, phosphates, or other inorganic agents, modulates the porous oxide surface to enhance water affinity in non‑image areas and improve coating adhesion. This is the hidden contract between aluminum and chemistry that makes offset lithography work: oil-based ink in the image, water film in the background, and the two kept apart by a microscopic landscape engineered on the metal.

The Three Plate Families: PS, CTP, and CTCP

From the press’s perspective, all plates do the same job. From the plate maker’s perspective, they live in different worlds.

PS plate – the analog workhorse

Positive or negative working PS plates are coated with light-sensitive layers designed for ultraviolet exposure using traditional plate-making units and film. The coating is usually a diazo-based or photopolymer system that changes solubility when exposed.

Positive PS plates

The exposed areas become more soluble and wash away during development. The remaining coating forms the ink-receptive image. These plates are favored for their forgiving tonal response and are familiar in many conventional shops.

Negative PS plates

The exposed areas harden and remain on the plate, while unexposed regions wash away. Negative plates often offer stronger image durability and are useful for long runs.

CTP plate – direct digital precision

Computer‑to‑Plate transformed how plates are made. No film, no separate exposure frame; the laser in the platesetter writes the image directly onto the plate.

Thermal CTP plates

Use a thermal-sensitive coating responsive to infrared laser (typically around 830 nm). The coating undergoes a chemical or physical change, allowing developers or water to remove non‑image or image areas depending on plate type. Advantages include excellent stability, high resolution, and consistent dot reproduction, critical for stochastic and high-screen ruling work. Processless or chem-free variants rely heavily on elaborately tuned coating chemistry that breaks down or disperses in the fountain solution on press.

Violet CTP plates

Respond to violet laser (~405 nm). Their photopolymer coatings are different but rely on the same base aluminum preparation. They tend to be fast and economical, often suitable for high-volume newspaper and commercial printing.

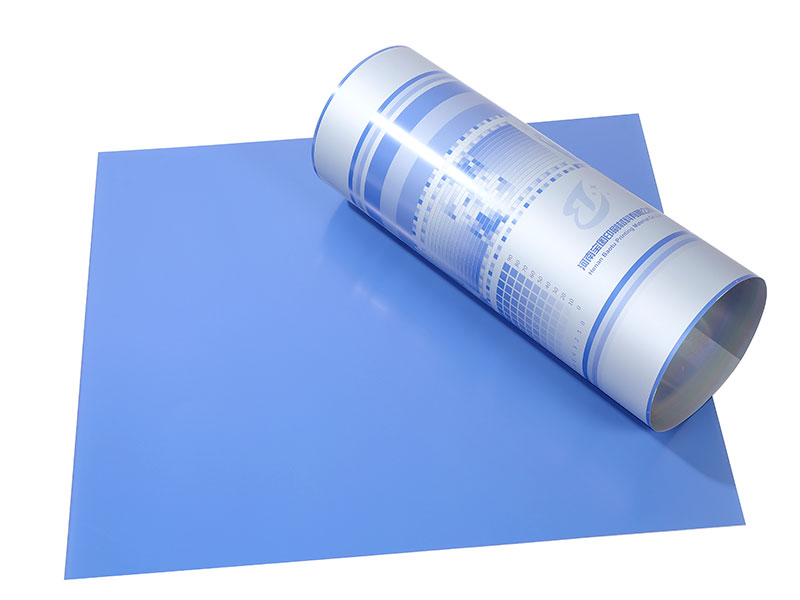

CTCP plate – the bridge between worlds

Computer‑to‑Conventional (CTCP) plates are interesting because they merge CTP-style digital exposure with UV or violet-sensitive coatings that can often be processed with more conventional chemistry. They are exposed with UV or violet lasers rather than thermal, making them compatible with some repurposed film imagesetters and lower-cost plate recorders.

From an aluminum and anodizing standpoint, CTCP plates are not dramatically different; the real difference is in the design of the photosensitive layer. That outer coating is tuned to respond cleanly to CTCP wavelengths, with strong contrast between exposed and unexposed solubility and robust adhesion to the anodic oxide so that high-speed offset runs remain stable.

Matching Plate Characteristics to Real-World Press Conditions

When choosing between PS, CTP, and CTCP plates, it helps to step beyond marketing labels and think in terms of metal, surface, and chemistry.

Run length and abrasion

Thicker, harder anodic layers with optimized alloy composition deliver higher run lengths and better scratch resistance. For newspapers or long-run packaging, the plate producer will typically increase anodic thickness and adjust anodizing parameters such as voltage and time, sometimes with refined alloy composition to maintain toughness.

Water balance and ink compatibility

The graining pattern and hydrophilic post-treatment drive how a plate behaves on press. A well-controlled electrochemical grain with consistent Ra and Rz values gives predictable water film thickness, especially critical for alcohol‑reduced or alcohol‑free dampening systems. The hydrophilizing chemistry must withstand modern fountain solutions, which can be more aggressive than older generations.

Resolution and dot stability

In PS plates, UV coating chemistry and exposure conditions dominate resolution. In CTP and CTCP, the laser spot size, beam profile, and coating sensitivity work together, but the micro-topography of the aluminum contributes to dot edge smoothness and halo behavior. Fine screening techniques, such as FM or hybrid screening, place greater demands on grain uniformity and anodic integrity than coarse AM screening.

Environmental and processing considerations

Processless thermal CTP plates shift much of the chemical complexity into the coating itself, relying on the aluminum’s anodic layer to remain stable in a wider range of fountain solutions rather than dedicated developers. In contrast, conventional PS and CTCP plates involve developers and finishers that interact with the anodized surface; if the underlying oxide is poorly formed or contaminated, issues like background toning, scumming, or plate blinding can appear on press.

A Hidden Partnership: Metallurgy, Chemistry, and Digital Control

What makes a modern digital printing plate distinctive is not just that it carries a laser-imaged dot pattern. It is the seamless combination of:

- A carefully selected aluminum alloy in a controlled temper, thin yet stable.

- Precisely grained and anodized surfaces that create the hydrophilic and mechanical backbone.

- Tailored surface treatments that tune water interaction and coating adhesion.

- Sophisticated photosensitive or thermal layers that respond to PS, CTP, or CTCP exposure technologies.

Seen from this perspective, a “Digital Printing Plate For Offset Printing Machine PS CTP CTCP Plate” is not a category label so much as a multi-layer engineering solution, where every stage from casting to rolling, graining, anodizing, and coating is tuned for the specific imaging system and press conditions.

If a shop experiences inconsistent dot gain, scumming, or premature plate wear, the answer is often searched for in laser power, developer temperature, or fountain solution dosing. Yet many of those symptoms trace back to the quiet core: alloy cleanliness, oxide thickness, and surface topography. When these metallic and chemical foundations are right, PS, CTP, and CTCP technologies all reveal their potential – delivering stable, high‑resolution prints, predictable color, and the long, trouble‑free runs that keep offset printing competitive in a digital world.